The first Baron Rothschild (1840-1915), founder of The Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company Limited. The illustration is reproduced with grateful acknowledgement to Mr Alfred Rubens.

The first Baron Nathaniel Mayer Rothschild (1840 – 1915), was a British banker and politician from the well-known Rothschild family.

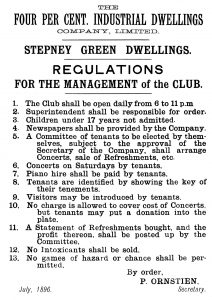

He became a member of the House of Lords when he was created Baron Rothschild. As a religious Jew, he held honorary positions in many Anglo-Jewry institutions and was involved in many philanthropic activities. He was heavily involved with the foundation of the ‘Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company’, a model dwellings company whose aim was to provide decent housing, predominantly for the Jews of Spitalfields and Whitechapel. The name was subsequently change in 1952 to the Industrial Dwellings Society (1885) Ltd and continues today as the IDS, a registered housing association providing accommodation at fair rents to those most in need.

The background

During the 19th century, London’s East End was at its most dangerous; badly overcrowded with most of its population living in ramshackle and insanitary housing.

This was later compounded by the arrival of Russian Jewish refugees; many of whom were fleeing from persecution in their homeland. At the heart of the Spitalfields area was, according to an observer, ‘the foulest and most dangerous street in the whole metropolis’. At the time, neither Government nor local boroughs provided housing.

‘Spitalfields hosted the Protestant Huguenot silk weavers, the Irish, as well as the Jewish community.’

The East End has always been a place of shifting populations, the first port of call for those fleeing persecution or war. Spitalfields hosted the Protestant Huguenot silk weavers, the Irish, as well as the Jewish community. Persecution and massacre of Jews in Europe worsened, leading to fresh waves of immigrants. In 1859, the Jewish Board of Guardians was founded to tackle the problems facing the Ashkenazi immigrants; focusing its efforts on the East End and aiming to provide for the impoverished incomers through the community’s own charitable funds.

By this time, the slum crisis was beyond control; the Board’s Sanitary Commission reported in 1884 that ‘the houses occupied by the Jewish poor […] are for the most part barely fit, and for the many utterly unfit for human habitation’.

The need and response

Charlotte de Rothschild Model Dwelling: the first estate built by the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company Limited. Opened in 1887 it consisted of 228 flats after alterations to the original lay-out.

A report, commissioned by the United Synagogue to enquire into the East End’s ‘spiritual destitution’, recommended two aims to remedy the situation: new settlers should be integrated into the ways of life of their new country and should be provided with decent, healthy homes.

These homes were believed to ‘constitute the greatest of all available means for improving the condition, physical, moral and social of the Jewish poor.’ Investors in the scheme were promised an annual dividend of four per cent from the 1,600 shares of £25 each, while rents were fixed at no more than five shillings per week. This was a lower return than what other social housing projects offered, but was ultimately designed to keep the rental charge low.

‘Investors in the scheme were promised an annual dividend of four per cent from the 1,600 shares of £25 each, while rents were fixed at no more than five shillings per week.’

The report was presented in March 1884 to the United Synagogue which fully approved its suggestions, and six days later the new Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company was formed at Nathan Rothschild’s City banking house. The, now-demolished, first Industrial Dwellings block was the Charlotte de Rothschild Dwellings in Flower and Dean Street, Spitalfields, built between 1886/7. It provided two-room flats with shared toilets and kitchens along with sculleries, balconies and attic workshops – all luxuries unknown in the East End slums and very desirable despite the block’s dull utilitarian appearance.

Navarino Mansions – celebrations for the silver jubilee of the Coronation of George V and Queen Mary in 1935

Community growth and expansion

The list of applicants for flats was inevitably oversubscribed and most of the new inhabitants were Jewish immigrant workers. By 1899, the Company had housed over 4,000 people and the death rate in their tenements was a third of the average in Whitechapel. The Company’s work soon expanded to other parts of London, including Camberwell and Hackney.

‘By 1899, the Company had housed over 4,000 people and the death rate in their tenements was a third of the average’

Coronation and Imperial Avenues off Stoke Newington High Street were completed in 1903, and the 300 flats of Navarino Mansions were built during 1903-1904 in an attractive Art Nouveau style with Art Deco features designed by the Company’s architect, Nathan S Joseph. Joseph’s work was known by the use of red bricks and lots of decoration, presumably in reaction against the dismal style of the first Spitalfields building, but after 1905 the Company halted building more blocks until 1934, when the economic situation forced them to explore using more economic construction methods.

The first new project was Evelyn Court in Amhurst Road. It was named to commemorate the death of Evelyn Achille de Rothschild, the great grandson of Nathan Rothschild, who was killed in action during the First World War in 1917.

A tenant’s story

A trip down memory lane – Vera Noyes’ story

I was actually born at home in Navarino Mansions in 1923, the youngest of five children. My parents moved into the flats in about 1911, having then only two children. However, when I was born, they were given one of the large, so-called “attic” flats, of which there were only eight on the estate. We were extremely fortunate as we were never cramped or overcrowded as so many families were at that time. We only had gas installed in the flat – no electricity, hot water, bathrooms, central heating, lifts etc. Coalmen had to carry coal up to all floors and were usually given two old pence per hundredweight sack for the delivery charge! Even as a baby, my pram had to be carried up 66 steps to our top floor flat – no pram sheds then.

Growing up, I had plenty of playmates – most families had three, four or five children in the early days. We were allowed to play in the two main avenues but we were never at a loss to amuse ourselves – there were seasons for every game – skipping, marbles, conkers, hopscotch, 5-stones, whips and tops, hide-and-seek, etc, but no ball games or bicycles were allowed. There were far more rules and regulations in those days – you had to be upstairs in your flat by a certain time each day – if not, the porters came after you! – and never allowed downstairs to play on a Sunday. Tenants also had to confirm to certain rules – each flat taking turns in sweeping and scrubbing their landing and two flights of stairs down to the next landing. Rent also had to be paid to the superintendent in the office on a Monday, and, if it wasn’t, you had a reminder from the office later the same day.

Looking back, I realise how happy we were as children playing together and not conscious of any differences. When the war came, many of us were evacuated with our various schools. I was only away for a year, having taken the school certificate in 1939. During that year, my parents and one sister still at home moved down a floor to another flat with only two bedrooms which was easier to heat. I certainly missed the spacious flat but it meant fewer steps to go down to the shelters which had been built under the four front lawns. Even in the shelters, the good community spirit among the neighbours continued.

Now at 94, I’m still living at Navarino Mansions and in the same block that I grew up in. It gives me pleasure looking back and sharing these memories with IDS.’